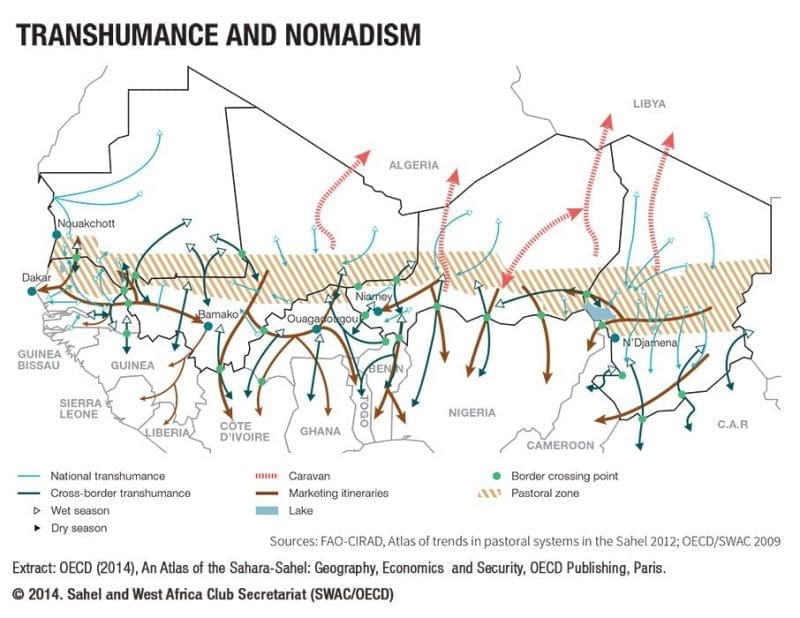

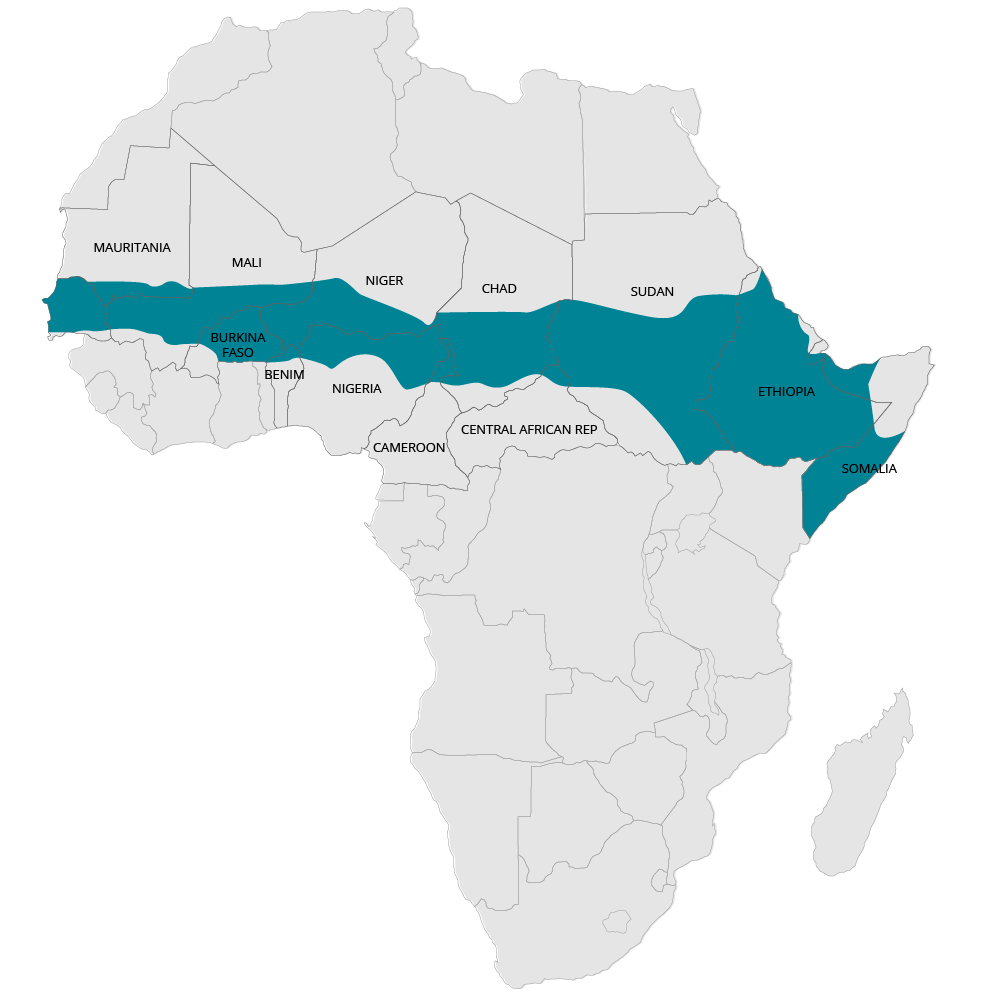

Pastoral migration routes traverse national borders and administrative divisions, building regional networks for rural food production and trade. The basic reason for practicing pastoralism is that grazing resources in the Sudano-Sahel vary significantly throughout the year. The distances between available resources at different times in the year means that transhumance is necessarily cross-border, a fully regional subsistence practice. Numerous regional agreements exist to promote increased economic integration, but each requires application by national government and provincial administrations.

The movement of livestock from grazing lands to urban markets creates value chains that connect producers, herders, buyers and sellers along the way, across borders and between states. Pastoralists benefit by accompanying their livestock directly to regional markets, eliminating transport costs and heavy logistics. Along the way, small-scale trade with local farmers and their communities adds to the regional value chain. Such exchanges may involve the sale of crops or animal products, livestock feeding on crop residuals, or the fertilizing of local crops with manure. Heavy livestock losses due to disease, theft or violence can mean disrupted meat supplies to major capitals, or trade delays in neighboring countries.

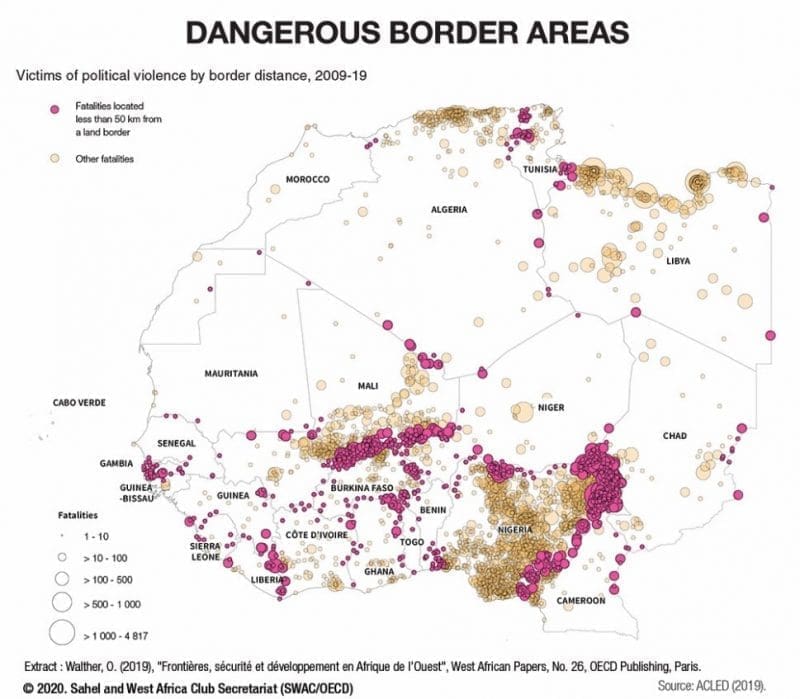

The flow of people and livestock across porous borders, however, also has implications for regional security. Border regions across the Sudano-Sahel have become focal points for criminal and insurgent activity. The productive connections made by livestock are disrupted by border closures or other measures aimed at countering transnational armed conflict, terrorism and smuggling networks. While some pastoralists have been implicated in cross-border crime, closing borders to transhumance has a wide-ranging impact, including on local farmers or traders whose prosperity depends indirectly on the circulation of livestock. The economic consequences of border closures are as devastating as terrorism or COVID-19, according to some researchers.

The long-term viability of cross-border pastoralism as a production system depends on the application of a consistent framework across the wider region. One country’s decision to restrict mobility can impact the economic welfare of its neighbors. For this reason, various regional bodies have proposed and developed multilateral agreements to support and regulate transhumance. These frameworks aim to smooth border crossings by replacing ad hoc regulations with consistent policies that are easily followed and implemented at all border posts among participating member states. However, in practice, these frameworks frequently fall short of effective implementation.

The social and economic value of pastoralism as a regional linkage is enshrined in numerous multilateral agreements, declarations, and policy frameworks.

- The ECOWAS Transhumance Protocol (1998) and the Regulation (2003) on its implementation, has been a guiding model for the regulation of transhumance in the region. The Protocol and the Regulation guarantee the free movement of livestock between Member states and outline regulatory practices governing travel itineraries, registration of herds, animal health requirements, and the resolution of conflicts.

- The Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) Protocol on Transhumance (2020) similarly enshrines the free movement of livestock within the IGAD region and calls upon Member States to set in place provisions to regulate herd movement and support and protect pastoral livelihoods.

- The African Union Policy Framework for Pastoralism in Africa (2010) is the first continent-wide agreement to call for protecting the rights and livelihoods of pastoralists and emphasizes that transnational character of pastoralist systems requires harmonized, regional approaches.

- The Declaration of N’Djaména (2013), produced as the outcome of a convening of Sahelian states, issued a call for improved international cooperation in support of cross-border transhumance. This was followed up by the Declaration of Nouakchott (2013), a commitment by six Sahelian states (Burkina Faso, Mali, Mauritania, the Niger, Senegal, Chad) to increase pastoral production, including strengthening regional cooperation and cross-border transhumance.

- Various bilateral agreements also set out provisions for cross-border transhumance between states. Mali has negotiated such agreements with four of its neighboring countries, and in 2003 the governments of Niger and Burkina Faso signed a memorandum of understanding that implements the provisions of the ECOWAS Protocol. In Sudan, the protection of livestock corridors and cross-border mobility is specifically referenced in the Darfur Peace Agreement (2006) and the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (2005).

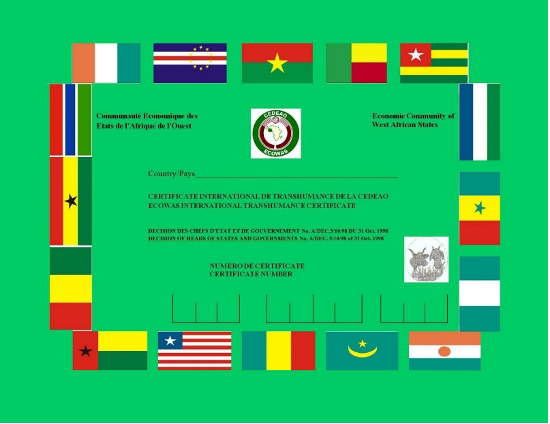

In 1998, ECOWAS was the first regional organization in Africa to adopt legislation governing the passage of livestock between member states. This Transhumance Protocol guaranteed the right to free passage of all animals (cattle, goats, camels, horses) across the borders of Member States. This right, however, was conditioned on adherence to a new regulatory framework – pastoralists were required to obtain an International Transhumance Certificate (ITC)*, enter and exit only through approved border checkpoints, and adhere to the restrictions on the timing and location of migration implemented by each Member State. The implementation of the Protocol has varied between Member States, as some have integrated its provisions into national policies (e.g., Niger) while others have not (e.g., Nigeria). Pastoralists and border agents alike are often unfamiliar with provisions of the Protocol. Even those who are willing to participate may face obstacles to obtaining an ITC, as many border regions do not have veterinary services or border outposts that are set up to issue or update the ITC.

*The ITC is a kind of passport that outlines the composition of a given herd, their itinerary, whether they’ve been vaccinated, and other details.

Photo: Pastoral livestock at a market in the Sahel. Credit: Shidiki Abubakar Ali

Pastoralists’ migration routes have long taken them across political borders, but these movements have become delicate affairs as states increasingly regulate migration for security or political reasons. Movement across contested borders can be a trigger in wider inter-state conflict, particularly when cattle are escorted by armed guards. Community leaders have played an essential role in ensuring that regular cross-border migrations can happen peacefully by negotiating agreements or open channels of communication between migrant and host groups. Tensions over the Sudan-South Sudan border provide a perfect example. Arab pastoralists from Western Kordofan, the Misseriya, have historically grazed their cattle in Bahr al Ghazal, a border state in South Sudan. Hostilities and bloodshed with resident Ngok Dinka forced the border to be closed until 2014, when both parties met to find agreement on transit routes and compensation for violence. External interventions can play a role in facilitating peaceful cross-border migration by creating space for communities to meet and negotiate.

The 2011 establishment of an international border between Sudan and South Sudan raised new challenges for the pastoralist and sedentary communities who had long been neighbors but had become polarized during the civil war. The border cut across traditional cattle migration routes, creating a new legal and political barrier for northern pastoralists and cutting off southern communities from their usual sources of meat and milk. In response, traditional leaders formed Joint Border Committees that could adjudicate issues relating to seasonal migration (cattle theft, crop damage, killing). In addition to the work of these Committees, a series of pre- and post-migration conferences were organized in various states along the border. These conferences provided an opportunity for community leaders from local tribes, government officials, the Joint Border Committees, and women and youth associations to discuss the logistics of the seasonal migration (timing, routes, grazing areas) and address lingering grievances or concerns.

Photo: Cattle walk along a dirt road in contested Abyei region. Credit: Ashraf Shazly/AFP via Getty Images

Many of the borderland regions that have long been pathways for pastoral livestock have become a key nexus for transnational crime and insurgency. Regional counterterrorism frameworks, such as the G-5 Sahel, multi-state administrative entities, such as the Liptako Gourma Authority, have responded to the need for a coordinated approach to security. Yet such coordination is often limited to armed forces and state governments, when it could be extended to civilian actors who support regional security. Facilitating the safe and legal movement of livestock requires a regional security architecture that engages the community leaders who have long played a leading role in negotiating livestock migrations, mediating conflicts, and protecting livestock against theft (see Module – Law Enforcement and Counterterrorism).

Pastoralism-related conflicts have been a key focus for the conflict monitoring systems embedded within regional multilateral institutions in West and East Africa. ECOWAS’ Early Warning and Response Network (ECOWARN) and IGAD’s Conflict Early Warning and Response Network (CEWARN) were both established to provide analysis for Member States on security concerns that fall outside of the jurisdiction of any one state. Monitoring cross-border pastoralism-related events was the primary mandate for CEWARN during its first decade (2003-2012). Both systems rely on a network of local monitoring units who report identified risks of conflict back to a central hub, where that data is used to inform relevant authorities in Member States. The success and effectiveness of these mechanisms depends substantially on the capacity and interest of these local units. Since many of the remote borderlands that are monitored by these systems are beyond the reach of the central authorities of the Member States, local units and partnering civil society organizations are critical to implementing effective responses.

Pastoralism’s contributions to rural economies are poorly documented and understood. For centuries, transhumance has linked multiple nodes of regional commerce across the Sudano-Sahel. Livestock raised in the drylands of Niger or Mali are moved south to access wetlands or markets in coastal states like Nigeria and Benin and as they travel they generate revenue and value through payment for veterinary services, trade with local farmers, or providing fertilizer for crops. This intra-continental trade is essential for satisfying the increasing demand from urban centers for meat products and adds value to agricultural production that would not come from ranching or other modes of production. The total value add of this economic activity is often difficult to quantify, as informal contributions such as manure can be substantial but not readily reflected in existing data. Producing and disseminating accurate information about the role of pastoralism in regional value chains is essential for policymakers and investors to make informed decisions about how they can support the livestock sector.

Some researchers have begun to capture the economic contributions of pastoralism that are not easily quantified due to the challenges of collecting data on informal economic activities. In 2015, for example, the International Institute for Environment and Development supported a series of nine studies conducted by Kenyan and Ethiopian university students to employ different approaches to measuring the “total economic value” of pastoral production in the Horn of Africa. Their findings shed light on the ways in which pastoralist activity supports other traders and livelihoods and contributes to public revenues.

Photo: Milk from pastoral livestock is essential for meeting rising regional demand while also supporting local livelihoods. Shown here Malian pastoral woman milking a goat. Credit: Leif Brottem