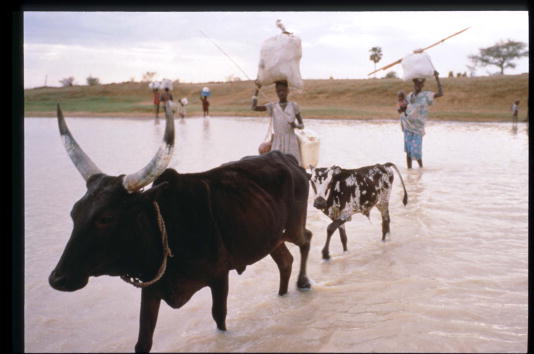

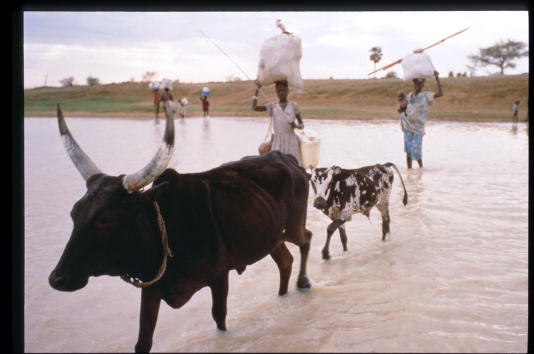

Women are agents of change, resilience, and development in pastoral societies. They play key roles in pastoral value chains, including milk processing, local commerce, and managing small ruminants. Yet, across the Sudano-Sahel, rural women are sparsely represented among governing bodies, trade associations, and customary institutions that handle disputes, negotiate access, and manage natural resources. Though pastoralists and other rural women often have fewer opportunities for leadership as authority figures, they exercise influence in other ways. Pastoralist women are more likely to stay behind in villages or home areas to manage household and economic affairs while their relatives take the livestock on migration, leaving them to maintain social and economic bonds with neighboring farmers and shape the beliefs and attitudes of the youth who also remain behind.

Despite their leadership in community affairs, women’s voices often go unheard as most interventions give undue weight to the role of traditional authorities. Engaging pastoral women as allies and direct beneficiaries in programming can be difficult, as access must often be mediated through traditional (and generally patriarchal) institutions. Their distinct experiences as victims of violence receive little attention: as victims of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) domestically and during conflict; or, as the ones left to provide for their family with limited trade skills and livelihood opportunities when their men are killed in conflicts. But women are more than victims. They are also social influencers who can support reconciliation or act as spoilers. Though women are rarely combatants in violence between pastoralists and farmers, their voices can incite or dissuade violence in others.

At the same time, traditional culture and gender norms can also contribute to conflict dynamics involving pastoralists, where ideals of masculinity shape expectations of how livestock, clan, and family must be defended. In some pastoral cultures, youth conduct cattle raids as a rite of passage to manhood and to acquire chattel to pay a bride price and marry. Such violence can trigger repeat cycles of theft and retribution between communities, perpetuated by traditional values and gender roles.

Women are equal stakeholders in the use of rangeland resources, yet their voices are generally not represented in the state or community-led institutions that manage these resources. Women constitute a significant proportion of subsistence farmers and participate in pastoral livestock production as both caretakers and sellers of animal products. When they are left out of decision-making processes, efforts to reform land tenure or mediate resource disputes are less likely to serve the interests of the whole community. When external interventions recognize the traditional barriers to the inclusion of women in both formal and informal governance, they can play a valuable role in opening opportunities for women’s leadership.

Beyond the inherent value of engaging all community stakeholders in resource governance, women can bring experiential knowledge that is critical for decision-making. In Chad, the Association des Femmes Peules and Peuples Autochtones du Tchad led a process to create a 3-dimensional map of local resources and migration corridors to guide policymakers on effective land management. The participatory process that created this map incorporated local insights and data shared by community leaders. After an initial map was developed by the male leaders, women were invited to review. They quickly began correcting the location of water points and other resources, recommendations that were later validated by their male counterparts.

Women’s channels of influence in community affairs are rarely reflected in customary leadership or state institutions but can constructively influence peacebuilding efforts. Too often, “leaders” are seen as those who hold official authority rather than those who have the capacity to influence those around them. This limited understanding of leadership can sideline women, who often have limited access to public leadership roles but still exercise significant influence. Women who lack official roles or positions may still be mobilized as mediators, emissaries, or peace advocates. They can play a role as a bridge-builder between pastoralist and agricultural communities, leveraging their social and economic ties with women in other communities who are also absent from formal peacebuilding or governance activities. However, building partnerships with women within pastoral communities can be challenging for outsiders. Most of the ways of establishing communication channels and making connections (e.g., through traditional leaders or trade associations) are dominated by men.

To address ongoing conflicts between pastoralist and farming communities in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, the UN Development Program (UNDP), UN Women, FAO, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) launched a joint program to strengthen the role of women in resolving intercommunal conflict. Women leaders in Taraba and Nasarawa states organized town hall meetings that brought together women from across different ethnic groups, including Fulani herders and Tiv farmers, which were later expanded to include men. The short term results of these dialogues have been mixed, but the initiative has helped to carve out greater formal recognition of the role of women in mediating conflict. In 2020, for example, the Taraba state government budgeted funds for the first time to support the UN Women, Peace, and Security Agenda.

In Cameroon, women play influential roles in ensuring good relations between pastoralists and Gbaya farming communities. Mbororo women solidify their economic ties with their Gbaya friends by trading the milk from their livestock for vegetables before they take it to market. Gbaya women have also played a critical role in peacebuilding as practitioners of Soré Nga’a mo, a ritual practice in which a cocktail of Soré leaves and sacred water is sprinkled across people or a village. The ritual is used in a variety of contexts – resolving conflicts, reconciling with enemies, legitimizing local authorities, or purifying a village after conflict or natural disaster – and illustrates one way in which women have traditionally exercised influence as peacebuilders. In the early 1990s, for example, the practitioner Koko Didi was called upon by government authorities to perform the ritual to help end ongoing conflict between the Gbaya and Fulani communities. In addition to the ritual performance, Koko Didi served as part of a reconciliation commission between the two communities that facilitated an end to the violence.

Rural and nomadic populations are often far removed from the legal and medical services offered to victims of SGBV. SGBV is an all-too-common occurrence among many rural women and can be yielded as a weapon in hostilities between pastoralist groups, or between pastoralists and settled communities. Absent legal systems to hold perpetrators to account, SGBV can add fuel to cycles of retaliatory violence. Securing justice and accountability is a social and legal challenge in weak and fragile states as it requires accountability for acts of SGBV to be an accepted norm and public institutions that recognize it as a crime. A multi-sector, holistic response to SGBV in pastoral rangelands may require mobile courts or legal services and awareness-raising programs that are adapted to pastoral realities.

With a limited body of empirical research and few opportunities for pastoral women to share their perspectives with national and regional audiences, government officials and aid practitioners often lack firsthand evidence to guide their policies and programs. Improving understanding of the role of women and gender norms by supporting locally-led research and the inclusion of women in public diplomacy activities is an essential starting point.

In 2010, a group of pastoralist women from 32 countries (including Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mali, and Niger) gathered in Mera, India to increase the recognition of women’s voices in the development of pastoralism policies and issue a global call for action. The resulting Mera Declaration called on governments to accept 23 points, including recognizing pastoralists’ role in environmental conservation, ensuring the equal rights of pastoral women, creating specific policies to assist pastoral lifestyles, and giving equal representation to pastoralist women. The Declaration was a novel concept as the first such statement that specifically focused on the role of pastoralist women, though it is not yet clear whether it has effectively catalyzed policy change in the Sudano-Sahel.